The Later Years (6-18)

Dentists recommend that money from the Tooth

Fairy isn’t used to buy lollies.

Photo courtesy Tracey Devereaux Photography.

Financial literacy has been part of the national school curriculum for primary and high schools since 2008. Given the pressures on the education system, and teachers in particular to be constantly including new information in schools, I think relying solely on them to make our children financially literate is silly. Sure, teachers can reinforce the right attitudes and teach the theory, but the practical lessons must be taught at home.

Teaching kids about money

Money skills seem to be waning in the collective knowledge of our community, and one of the reasons for this is because of the way in which we use money and show our kids how we use it. Years ago, before the popularity of credit and debit cards, you would receive your pay in cash and pay for stuff the same way. Growing up, I remember seeing cash changing hands when Mum did the shopping. Nowadays, kids witness their parents taking things off the supermarket shelves, putting them into a trolley and briefly tapping a small piece of plastic, and more commonly their phone, at the checkout. They see nothing change hands and also don’t see the amount of money in a wallet getting smaller (or the pile of debt get larger). It’s the way we do things.

I recall Paul Clitheroe, who you reckon would have kids who themselves are financial savants, say that his kids had no concept of the link between work and money. When he asked one of them where money came from, they replied “The ATM.” If my kids ever say something like that I’ll belt them.

FURTHER READING:

The only finance book written for kids (yes, kids. It includes stickers!). This book compliments Scott Pape’s bestsellers The Barefoot Investor and The Barefoot Investor for Families and, like the others, is also a bestseller.

Give your primary school age child money for the canteen or tuck shop (if their school has one) so they understand how far $5 goes. It’s best to limit this to once a fortnight or once a month so that your child views it as a treat, rather than something they expect all the time.

Case study

For lunch in primary school I would almost always have sandwiches (yeah, not much has changed!) but about four times a year we must’ve run out of bread at home, and I was given some small change for a pie from the school canteen. Back then you could get a pie and sauce for under $1.

I remember a kid in my class from a large family who were as poor as you could be. There were about six children in this family and from memory he never wore the full school uniform. Their car was a beaten up old station wagon that didn’t look roadworthy and I’m sure couldn’t legally fit them all in.

Seeing him eating a pie one lunchtime I asked him how much money he was given each day for lunch and to this day recall his answer – “A buck, sometimes two.” It was the perfect example of how we grow up learning about money from those most important to us.

One way to make it easy for your kids to understand the way money flows is to go old school. Take cash out of an ATM (not in front of your children) and put it into an envelope on the day you receive it. Write the date for the period the money represents on the envelope. For example, if you are paid fortnightly, for October write “1/10 – 14/10”, if you are paid monthly just write “October” on the outside. Then explain to your child where the money has come from (work, government, insurance, etc.) and that there is no more until the next payment.

One way to make it easy for your kids to understand the way money flows is to go old school. Take cash out of an ATM (not in front of your children) and put it into an envelope on the day you receive it. Write the date for the period the money represents on the envelope. For example, if you are paid fortnightly, for October write “1/10 – 14/10”, if you are paid monthly just write “October” on the outside. Then explain to your child where the money has come from (work, government, insurance, etc.) and that there is no more until the next payment.

Then go grocery shopping with junior (with a list) and concentrate on the unit pricing at the shops. Give the cash to them to pay at the checkout and as they hand it over, ask them to work out how much change there will be. You can even get them to check the docket to see if something has been mistakenly scanned twice.

Then go grocery shopping with junior (with a list) and concentrate on the unit pricing at the shops. Give the cash to them to pay at the checkout and as they hand it over, ask them to work out how much change there will be. You can even get them to check the docket to see if something has been mistakenly scanned twice.

Looking at the docket is a really quick way to see how expensive meat is compared to fruit and veg, and also that the mark next to an item, whether it’s an asterisk, a percentage sign or if it is labeled A or B, means it is more expensive because of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Suddenly they start to understand that chips and chocolate means more tax, which makes things more expensive.

You want to get the message across that you have a limited amount of money to purchase as much as you need, and that it’s not just one trip to the grocery shop that the money must be used for. Explain that there are a number of bills that need to be covered in that pay period, as well as other expenses you will be hit with soon that will need money set aside for from this pay. You’ll be teaching a number of important concepts all at once, especially budgeting, and probably honing your own skills at the same time.

When your child understands how cash flows to you and then from you on to others, you can then introduce them to how debit cards fit into the picture. They will probably need to have a basic understanding of maths to follow the idea of a changing balance on a debit card.

The above scenario may work for your children or you may find that they have a reduced care factor because the money is not theirs. Turn the tables on them!

I reckon it is better to teach addition and subtraction without the aid of a calculator, including the one in your phone. If you get into the habit of relying on a calculator and accidentally punch in the wrong numbers without doing the rough sums in your head, one day you will be ripped off without knowing it. Getting short-changed a couple of bucks in a convenience store is one thing, getting swindled thousands purchasing a car using finance is another.

A great book that is specifically aimed at parents of Aussie kids is Don’t Eat The Marshmallow by Robert Bihar. Bihar self-published this book which is available online for free.

Pocket money

Our chicken with her second beer.

She downed her first one too fast for

me to get a photo. She gets that trait

from her German side.

Whether you choose to pay pocket money for everyday household chores or not is completely up to you. Many people feel that doing chores is part of being in a household and that adults don’t get paid for it so why should kids. One way of looking at household chores is to break your life down into four distinct parts – 1st part is when you are too young to do chores (you create them for your parents), the second stage is when you are a kid and get paid for doing chores, the 3rd stage is as an adult where you do chores but don’t get paid for it, and the 4th is late in life where someone else gets paid to do your chores (like wiping your bum).

I really don’t like the idea of not giving pocket money at all (yeah, it happens) as the child is not exposed to all the good lessons that come with handling their own money. If you are involving your kids with a bit of hard yakka like painting the house or landscaping the yard then it’s only fair to reward their labour with cash. Or beer.

Some parents decide not to pay their kids for everyday chores, like doing the washing up and tidying their bedroom, but will pay them set amounts for larger irregular chores such as washing the car or mowing the lawn. You may decide to pay them $10 for raking the leaves but stipulate that they get no money if their bed is not made and the washing hasn’t been folded as well. If your children help you out by working in the family business every Saturday, don’t forget to pay them super. Even if they don’t work enough hours to legally receive it, the lesson they receive and the future compounding of the super will be hugely beneficial for them (more on that below).

You may choose to link pocket money, or bonus money to good and/or bad behavior or school results. Nothing like a bit of financial incentive to turn your under-achieving devil into a straight A’s angel. In theory, the incentive of $20 for every A and $5 for every B might help to improve their grades. However, if junior knows they are not on track to get a good result in one subject it may encourage them to stop trying and start concentrating on the areas where the money will come from. Solution – tax them for every subject they fail. It’s great for their mental health and self esteem.

One thing parents fret over is the amount they should be paying in pocket money. Should you go for a rule of thumb set amount, like $10/week for a 10 year old, $11/week for an 11 year old, etc., or should you be swayed by what your children’s friends are being given in pocket money? While it is totally up to you, I would suggest that before you are persuaded into keeping up with what the Joneses are paying to their kids, you ask yourself how financially literate the Jones family is. If your kids won’t accept that you pay  them less pocket money than what their friends receive, explain to your child “But you have a different boss.” This may incite a strike on their behalf, then a picket line where they yell abuse at the cheap child scab labour you have brought in to replace them. Hopefully it will all be sorted before it goes before the Fair Work Commission. If not, take your legal fees out of their future pocket money.

them less pocket money than what their friends receive, explain to your child “But you have a different boss.” This may incite a strike on their behalf, then a picket line where they yell abuse at the cheap child scab labour you have brought in to replace them. Hopefully it will all be sorted before it goes before the Fair Work Commission. If not, take your legal fees out of their future pocket money.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies says that 37% of 10 to 11 year olds receive pocket money. 94% of them have to do chores, 60% need to follow house rules, and 42% have to do their homework to get it. Half of those kids are paid between $5-10 per week. Source: Choice, May 2012.

Each of the above suggestions can only really work if you decide with your child’s other parent how you will do it. Even if you are not on good speaking terms with them, sorting out how the children will be dealt with in relation to money (and keeping it consistent from both parents) will make things much better for the child. How you do this in practice so that one or both parents are not trying to buy the child’s love is way beyond my expertise.

Twenty dollars paid this way can easily be split

into saving, spending and charity piles. A $20

note would need to be broken down by a child

at a shop with all its nasty temptations.

Whatever you decide and no matter your situation, it is best to strongly encourage your kids to save a decent percentage (20-50%) even if it means you will give them extra if they save well. By extra, I’m talking about interest if their cash is sitting in a piggy bank. You should be encouraging them to save a large percentage of their money (a much larger percent than what you are saving yourself) so that your kids can see a decent amount of money accruing in their bank account or piggy bank.

When you actually hand over the pocket money, rather than paying one large note, pay in denominations like in the photo on the right to make for easy dividing.

To reinforce the budgeting concept, pocket money should be a set amount paid on a set day (subject to penalties for misbehaving or not completing chores). Personally I believe connecting pocket money to work/chores or actually having to do something for it will help to reinforce the value of money. The child will appreciate the toy they buy with their own money more if they can link it to how hard and long they had to work to be able to afford it.

Every parent has or will experience a time when their children will want something that you are unable or unwilling to purchase for them. Finding a way to tell them they’re not getting what they want is difficult. Try reassuring them that you will always provide for their needs. As for their wants, you will show them how to save up for these things and pay from those savings in the same way that you do for things you want yourself.

Case study

Ben and Michelle have three boys, Jack aged 12, Charlie 10 and Hugo aged 8. The boys do not receive pocket money for doing everyday chores like cleaning their bedrooms as their parents view these chores as part of being in a family. However they are paid weekly for doing some of the bigger things around the house (e.g. bringing the washing in off the clothesline and folding it). Jack gets about $5 a week, Charlie is paid about $3 and Hugo is happy receiving a pile of 20 cent pieces. All three also receive money on birthdays from grandparents and other relatives.

They can spend their money on whatever they like (with guidance from their parents) so for the older two it generally means saving up towards a goal that takes a few weeks or months, while 8 year old Charlie feeds his sweet tooth.

Ben and Michelle have not put into place a strict savings regime where the boys are required to save part of their weekly cash into their bank accounts, but they are still instilling in them the discipline of saving. When the balance in their piggy banks reaches a decent amount (somewhere around the $50 mark) mum and dad tell the boys it’s time to whack half into the bank. The boys then take the money to the bank and deposit it themselves.

Although Ben and Michelle don’t follow a regimental regime with their boys, the most important aspects of saving, goal setting and the link between pocket money and work are all there.

So, your kids are too young to work and you don’t have spare cash to give them pocket money. What can you do? If you live on the mainland, your state has a container deposit scheme (if you are in Tassie start a pile of them now and you’ll have a garage full by the time your state pulls its finger out and gets Recycle Rewards up and running sometime in 2024.) These schemes mean that every eligible plastic, aluminium or glass container taken to a collection point is worth 10 cents each. That might not sound like much, but, as with all small amounts, it adds up. Especially if you target places like sporting or cultural events – take a big bag, wait for people to leave and make a small fortune picking up the resource left behind. Encouraging your child to earn some money while cleaning up the environment means everyone’s a winner.

The following video is about pocket money and it’s another one from the Raising Children website, so, just in case you missed it the first time….

Sourced from the Raising Children website, Australia’s trusted parenting website. For more parenting information, visit www.raisingchildren.net.au.

Make it fun!

It probably doesn’t take a genius to work out that I firmly believe learning should be fun. Yes, that’s right people, I don’t wear my undies on the outside standing next to Canberra’s busiest road whilst being 100% serious. The funnest way to teach kids financial skills is to do it in a way that they don’t even realise they’re learning. Yep, it’s time to play some games!

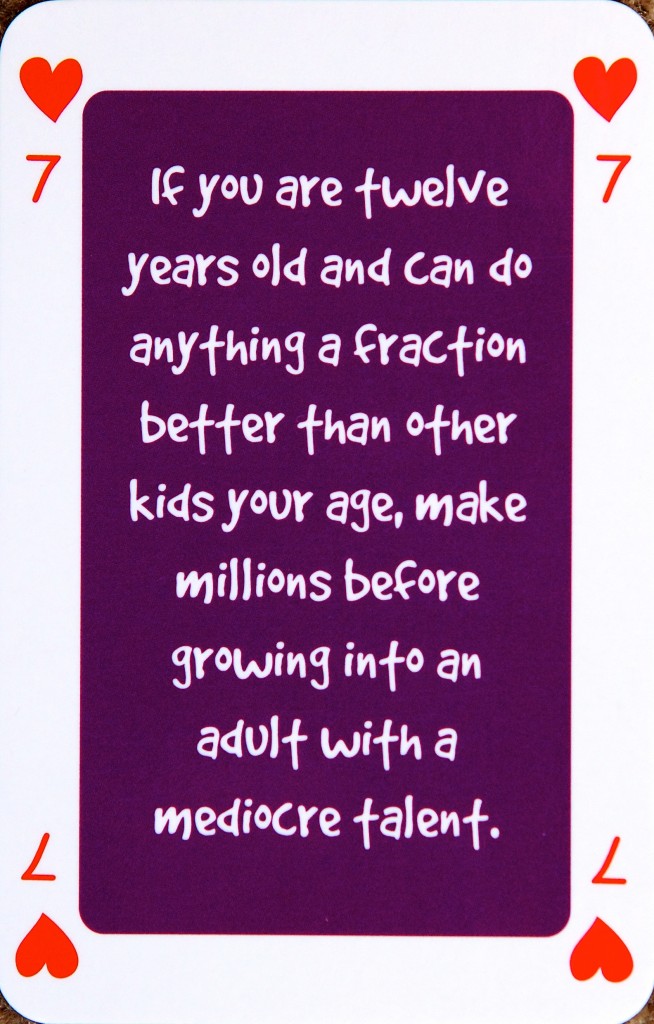

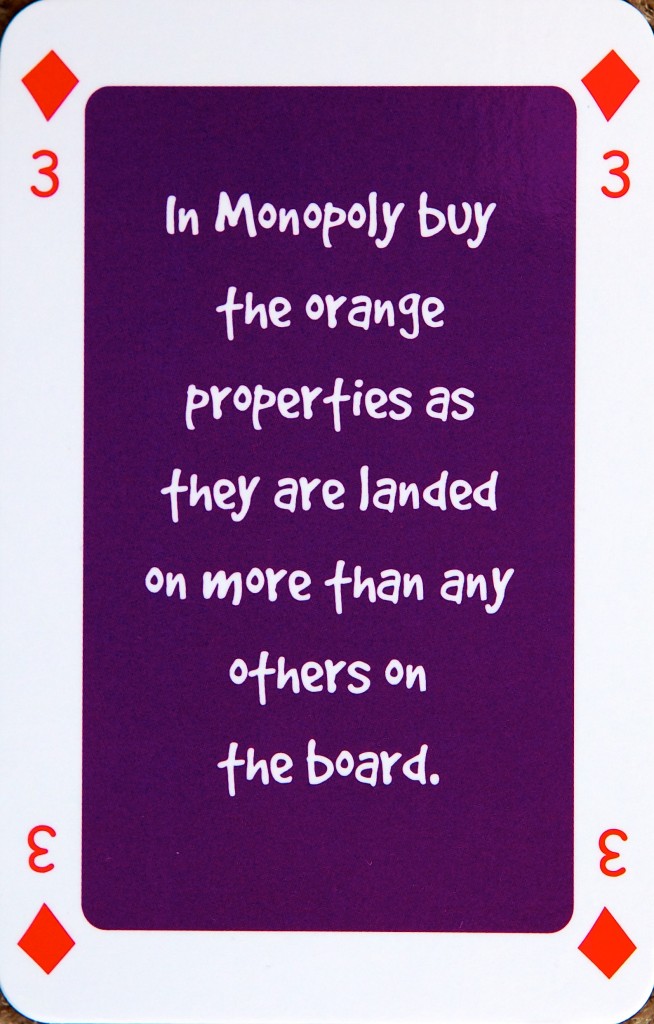

Families have been entertained (and had a few fights started) by playing Monopoly since the early 1900’s. It’s the classic money game which has not changed much since it was first released, and is available in many different versions, including a few Aussie versions, a Simpsons version and even a Star Wars version, if you’re that way inclined. Not only will playing Monopoly help with basic mathematical skills, but it will also get a few money messages across. When you play Monopoly, let your kids take turns being the banker.

Families have been entertained (and had a few fights started) by playing Monopoly since the early 1900’s. It’s the classic money game which has not changed much since it was first released, and is available in many different versions, including a few Aussie versions, a Simpsons version and even a Star Wars version, if you’re that way inclined. Not only will playing Monopoly help with basic mathematical skills, but it will also get a few money messages across. When you play Monopoly, let your kids take turns being the banker.

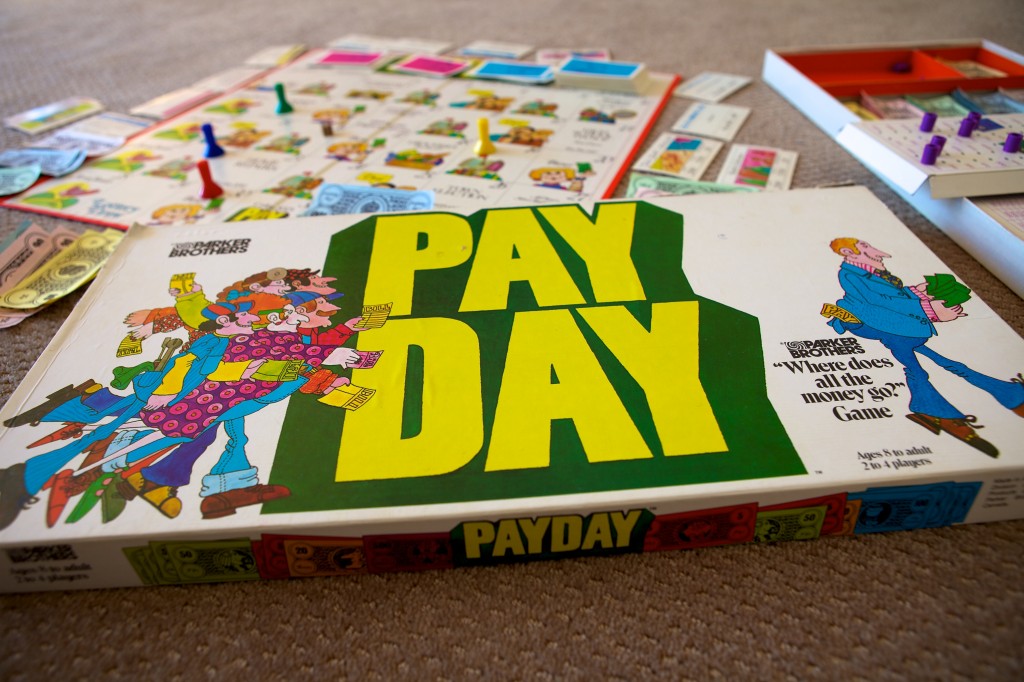

This is a well worn retro version of Payday, for

2 to 4 players, ages 8 to adult. We started playing

it with our kids well before they turned 8 and they

love it. If you can’t find a new one in a shop, you

should be able to buy a pre-loved one on eBay.

Another board game that never reached the heights of Monopoly’s popularity is a game called Payday. I absolutely loved playing this game growing up with friends and family (that news wouldn’t have shocked any of you I’m sure). Payday takes a different tact from Monopoly as it introduces a basic concept of investment risk and return, as well as monthly bill payments, interest (both earned on savings and due on loans) and insurance.

As far as board games go I’ve never played Cashflow 101, a game developed by Rich Dad Poor Dad author Robert Kiyosaki. I have looked over a friend’s copy of the game to discover the rules are 20+ A4 pages long. To say it’s rather complicated and, at $200+ plus postage, stupidly expensive, is an understatement. After reading his famous (and rather crap) book I won’t be rushing out to buy any of his products.

Being a mad keen card game lover I couldn’t mention games without talking up the good points of playing card games with your kids. I am yet to find a child who, after giving it a decent crack, has not enjoyed playing games like Canasta, Hearts, Spades, Eucre, 500, Uno, Knaves, Cribbage, Rummy and a heap of others (you might want to keep the kids away from Poker and Blackjack though). Whilst not directly related to money, playing card games is cheap, clean, thinking-related, non-electronic fun which promotes great basic mathematical skills, especially when it’s the kids who have to keep score.

Playing darts is also great for honing multiplication, addition and subtraction ability. Darts doesn’t just consist of the traditional 501 or 301 game you see in the pub, there are many different games to play using the same equipment, including Cricket, Killer and Around The World. Whichever game you choose, you just want to make sure that proper eye protection is worn. As the old saying goes – it’s all fun and games….

Case study

When my nephew Hayden was getting to the age where we were having trouble thinking what to get him for Christmas and birthdays, Claudia and I decided it was a good time for him to start a super account. For years our gifts to him consisted of a cheque made out to his super. It’s also an option for his other aunts and uncles who are scratching their heads thinking of a gift. The kick start to Hayden’s super will be great, especially with the bonus he has received from the superannuation co-contribution, as personal contributions are eligible for the co-contribution (for more on that, check out the Superannuation topic).

By the time he got his first full time job, not only did he not have to worry about filling in the super forms at the same time as all the head-spinning stuff that came with starting a new job, but he saw the benefits from exposure to growth assets and early compounding.

Superannuation

Opening a superannuation account is a good way to introduce an irresponsible teenager to something very adult. Teenagers are often described as wanting the rights of an adult while having the privileges of a child. Helping them to contribute amounts to a super fund will be a good lesson in the complexities of adult life whilst having the huge benefits of compound interest. They will be best off in a cheap industry fund with little or no insurance, as life insurance is not really necessary for under 18 year olds and will just chew into the small amount of money in their super.

A superannuation account must only be opened after gaining a tax file number. Actually, you can open one without providing a tax file number, but the tax office will withhold 47% tax from employer contributions if you don’t provide one, and only 15% tax if you do. Opening a super fund is a really great idea as soon as children have started working part time, even if they are working for a family business and their employer is you, or if their boss is not legally obliged to put money into super for them. The legal obligation for an employer to contribute to a minor’s super is where they work at least 30 hours per week – the same as for adults. The nice bosses will pay super for teens working part-time, regardless of the hours worked.

You don’t have to wait until your child has started working to begin contributing to super on their behalf, as some funds have no minimum age to open an account. But the rules covering when and how you can access super are exactly the same no matter how old the account holder is. If you decide to open an account for your son or daughter keep in mind that it will be a great lesson for them to be able to see the dollars going up over the years. However, like you, they will not be able to get their hands on this money until they retire.

Mobile phones

Claudia and I are fortunate in that most of what our kids do with mobile phones at this point in their lives is to listen to Spotify and take the occasional photo of one of their parents on the toilet. So if you have a completely different view of the way your teenager uses a mobile than as I have discussed below, then you likely know a crapload more about it than I do.

A teenager these days would rather have leprosy than be caught without a mobile phone. They probably could get away with being a leper given that all their friends would have their heads buried in their phones and wouldn’t even notice. This is a difficult area for parents – balancing what is a social need (a hot pink iPhone 15 Pro Max) with what is an actual need (dad’s old Nokia). I say need, but recognise that somehow we managed without so much as a walkie-talkie when us gen X and older gen Y people were at school.

I reckon the best way to stay out of trouble is to go prepaid or with a plan that cannot go into debt. Prepaid only works where a monthly limit is set at the beginning of the month and the phone is not topped up. If they get the privilege of using it, your teenage kids should be given the responsibility of paying the phone bill. This doesn’t mean that money for mobile bills should come out of their piggy banks, but that you should decide an appropriate amount for mobile spending and give that to your child so they can cover the bill and manage their usage and plan themselves. It’s up to you to decide when the money from their part-time job is enough to stop that mobile phone money coming from your pocket.

Charity

Australia is a very lucky country. You only need to spend one night struck down with gastro in Mexico City where the mains water is shut off daily between 10pm and 6am to work out just how lucky we are. But that doesn’t mean we are all sitting pretty all of the time. Aussies will really help out a mate in need when times are tough. You see evidence of this every time a natural disaster strikes. Be it bushfires, floods, cyclones or even a personal tragedy that pulls at the heartstrings, there are plenty of examples of people helping others in their time of need. This includes instances where kids have emptied their bank accounts to donate money to a disaster recovery appeal.

While giving away your last dollar might make shoving a camel through the eye of a needle look easy, a better compromise may be to have your child set aside a percentage of their pocket money. Whacking 5-10% of a child’s allowance into a jar for a charity of the child’s choosing will give them a real sense of helping others less fortunate. I reckon the best time to start is when the child understands what donating money means.

If you decide that a donation of money is not on the cards, consider encouraging your children to donate their time. Whether it’s helping an elderly neighbour or fundraising for their school, helping out will instill a concept of respect and assist their understanding as to how well off your family may be in comparison to others.

Pictured on the right is a tool that helped reinforce children’s thinking when it comes to setting aside money for charity. The Moonjar Moneybox encouraged children to split their money into three compartments: money for saving, spending and sharing. Unfortunately Moonjar they are no longer around, but you can do the same sort of thing by getting three glass jars and label them Spend, Save and Share. Spend is for blowing on whatever your child wants in the short term. Save is for longer term goals and Share is for giving away. The amounts that your child decides to allocate to each is up to them, but I would recommend an amount from each pay/allowance/pocket money is to be split to all three.

Kids And Money General Tips

- Join a toy library. Toy Libraries Australia is the peak body for toy libraries and have locations for all states and territories, and St Giles has a couple listed in Tassie.

- When investing for your children, or working out an inheritance for them, it may be a good idea to reflect on how the world’s richest investor, Warren Buffett views the subject. He has always said he would give his children “enough money so they would feel they can do anything but not so much that they could do nothing.”

- When your children go to buy their new toys, show them how to search different websites to find the best deal. Depending on their level of computer skill, they may be able to teach you how to do it better!

- Get your child to collect vouchers, coupons and specials from pamphlets/newspapers/dockets. Take these on your grocery shop and give a percentage of any money saved to the child.

- Small change that’s fallen from the pockets of clothing when doing the laundry gets to be kept by the child who does the washing. Washerwoman’s bonus, as my mum used to call it in the years before political correctness.

- If you have a garage sale to make some space at home, involve your kids in deciding what they can offer for the sale from the toys they no longer use. Get them to set the price for those items and take the money for the sales.

- Teens without ATM/debit cards cards should always have $10 or so in their wallet/purse as emergency for getting on public transport or for some food or a drink when they are stuck.

- Encourage your older teenage kids to save a set percentage of their pocket money in a savings account. Aim for something decent like 20-50% and which is not to be used for small purchases. This is the money that should be for their first car or house deposit – something big and long term so they understand that there are some things worth the wait. In this way they learn that delayed gratification is a wonderful feeling of achievement that helps to distinguish the difference between needs and wants. By giving something up in the short term they can end up with much more than they had before.

- If you know your child is going to make a (small) mistake with their money, let them. Small mistakes can be good lessons, big mistakes can really set them back and be disheartening. It’s up to you to decide the size that mistake will end up being.

- Involve older children with the family’s finances (insurance, car rego payments, rates, rent, mortgage, etc.) to give them an appreciation for the complexities of the family budget and what is to come for them one day.

- If your children are working full time and still live at home, charge them board. Use this money to boost your super. After all, the longer they live at home, the more money they will erode from your retirement.

You can probably see a pattern emerging here that so much of what is relevant for teaching children about the basics of money applies just as readily to adults. The concepts remain the same, only the delivery of the message changes.

And finally…

Any parent who has mistakenly sworn in front of their child will know how much children absorb from the role models they grow up around. They speak with the same mannerisms, have the same facial expressions and world views as their parents and will approach money in the same way too. Parents who are trying to instill in their kids good money skills, but who stop to grab a coffee on the way to dropping their children off at day care or school each day, will be giving a mixed message. You can guarantee that the message the kids will absorb will be the one they see over and over again, not the one that their parents are trying to teach through games, stories and concepts.

If you haven’t done so already, now might be the time to change a few things in your household and implement some of the things covered in the Savings topic. Even if when reading those suggestions you thought “But that stuff’s only for tight arses!” The truth is that saving money, and being seen to save money by your children is very important to pass on this knowledge to your kids automatically. If it is normal for them to put an extra jumper on when it’s cold inside, to have takeaway meals once a fortnight or less, to dry clothes on the clothesline and to drink water instead of soft drinks, your kids will be able to save without needing to think about it.

In essence, what I am saying here is that it doesn’t matter how closely you have read the content of this website. It is irrelevant how many facts and figures you are able to remember, and that you could now explain the basics of finance to a friend in a way that you may not have been able to previously. What matters to you, your partner, and most importantly to your children, is that you actually put into practice the lessons from Financial Freedom For Gens X And Y. If you don’t, not only have you wasted your time, but you will throw away tens of thousands, possibly hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years to come. And again, it’s not just your money you will be throwing away, but your children’s as well.

I guess it’s fitting that I should end this website where I began it – talking about learning money skills from the family you grow up in. Mahatma Gandhi once said something along the lines of “Be the change you want to see in the world,” which is kinda what you would expect from such an important and influential figure in world history. You don’t have to change the world (that’s not the homework I am setting for you). I reckon you could tweak Gandhi’s words so that they say “Be the change you want to see in your family.”

Thanks again for visiting my website (and getting to the end!) and I would really appreciate a link to my site when you are next on a forum answering a question someone has about where to find good information on money. Or just spam the crap out of your Facebook friends with my page. Even if they don’t appreciate it, I will!

Nick

The Later Years (6-18) Resources

- Barefoot Kids by Scott Pape

- Don’t Eat The Marshmallow by Robert Bihar

- Toy Libraries Australia

- Tasmanian toy libraries