Investment 2

Cash and Fixed Interest

Cash and fixed interest includes everyday accounts, term deposits and online savings accounts from banks and mutuals (credit unions and building societies), and government and corporate bonds. Bonds and debentures are loans you make to a government or a company for which they pay you back with interest. You could expect a return of anything up to around 4-5% per annum from these assets (largely depending on how high official interest rates are) and they are best used for placing money in the short term: 1, 2 or 3 years at the most.

The advantages of cash and fixed interest investments include the following. They are the lowest risk of the three asset classes. Accounts of Australian banks, building societies and credit unions, and subsidiaries of foreign banks, are risk free for deposits of up to $250,000 per person per institution as they are guaranteed by the federal government. (If you have more than $250,000, split your money across different institutions and your money is still covered by the guarantee.) This means that if the bank where your term deposit is held goes belly up, Anthony Albanese will give you a cheque for the amount in your account. Cash and fixed interest assets also have very low levels of volatility. They can be accessed very quickly so you can have the actual money in your hand or transferred to someone quickly. This is known as high liquidity. Liquidity is how quickly something can be converted to cash – the actual notes. The higher the liquidity, the faster you can get the cash. Another advantage is that the return for cash and fixed interest investments (which is the interest rate) is generally known at the time you invest your money and you can start a cash investment with as little as $1 in a savings account. But, of course, the bank fees would quickly eat that dollar.

The disadvantages include: The returns are the lowest of the three asset classes over the long term. Part of this reason is because they have no capital gains, which is also known as capital growth. $100 put in a term deposit 10 years ago would still be worth $100 now. It would have earned interest in that time but the actual amount put away would not be worth more. In fact, because of inflation it will buy less now than it could 10 years ago, and therefore means that cash and fixed interest assets are not good for protecting against the effects of rising prices. All income from these investments will be included in your tax return and taxed at your marginal rate. Cash and fixed interest investments can be too easy to access for people who can’t stop themselves from using an ATM, and there may be penalties for taking your money out of products like a term deposit before the maturity date. If you leave your money in a term deposit until maturity, then forget about it, your bank will automatically reinvest it for the same term but quite possibly at a lower interest rate.

Cartoon courtesy of Michael Mucci.

You can start an investment in cash or fixed interest a number of ways. The most obvious is to contact a bank or credit union and deposit some money into a savings account, cash management account or term deposit. This can be done in person, over the phone or through the internet. To invest in a debenture or deposit note you contact the company offering them directly, and make sure you read the prospectus they send you (you can find these companies by googling ‘debentures’). One way to invest in bonds is through a managed fund or a financial planner. A cheaper way is to buy bonds directly through the Australian Securities Exchange where they are referred to as Exchange-traded Australian Government Bonds. Learn more on the Australian Government Bonds site.

Property

The second asset class is property (or real estate). This includes vacant blocks of land, residential property (houses, units, townhouses, etc) and commercial property (which can be everything from a factory to a boot repair shop). You can expect returns of roughly 8-12% per annum on property over the long term. Property is a long term investment which should be held for 6-7 years or more so that any short term falls in price will be cancelled out by a longer term rise in value.

The advantages of property include: The returns are generally good over the long term and consist of both income in the form of rent (except for vacant land), and capital gains as an increase in the value of the property. Real estate does offer some taxation advantages, for example with depreciation and especially negative gearing, which I cover in the Taxation topic. Property is an asset that can be borrowed against and the capital gains mean it’s good for protection against inflation.

Claudia and I have friends who built a straw house (they’re not pigs). The recommended R value for insulation in their area is between R 1.5 and R 3.5 (a higher number means better insulation). Their straw house has insulation rated between R 11 and R 16.

Due to the advantages of property, Australians have a bit of a love affair with it. I blame pigs for this.

In particular, the third little pig, who decided to build his house out of bricks. The Big Bad Wolf huffed and puffed, couldn’t blow it down: “Oh bricks and mortar, safe as houses!” Every time I hear this story I think – “Go wolf, blow it down and shatter the illusion!”

Bloody emphysemic wolf.

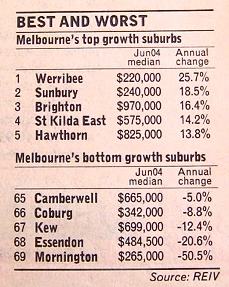

The disadvantages. Many people do not realise that the risk of losing money with property is quite high. This is illustrated in this table on the right of 12 month property returns in Melbourne suburbs to mid 2004.

Source: The Real Estate Institute of Victoria.

The best returns were in Werribee, where you would have been very happy to see an average increase in value of 25.7%. All of those top five suburbs had very good returns over that year. However, higher expected returns mean higher risk, which is reflected in the returns of the bottom five suburbs. All of these had an average negative return (in other words the values of the properties dropped) with Mornington suffering a massive -50.5%, and remember, that’s the average over that year, so some properties in Mornington dropped by more. Property can and does go backwards at times.

Unlike some cash and fixed interest products, the returns for property are not guaranteed. You require a lot of money to buy real estate, expect even the cheapest one bedroom unit in a dodgy area to set you back a decent six figures. Property has low liquidity, meaning it will take you anything between six weeks and 12 months between when you decide you want to sell and when you receive the money. I’ve sold three properties, one of them took four months for me to get the money, another took 11 months. You have no spread of your money from holding onto just one property (which is all most people can afford). Tenants can damage the property or not pay the rent on time or at all, and the property managers (assuming you go through a real estate agency for this service) may not perform the inspections you expect them to.

Your loan repayments can get out of hand, especially as interest rates rise and demand in the rental market falls. Although these ongoing expenses are tax deductible, you would have to pay for: rates, building insurance, maintenance costs, property management, body corporate costs, etc. If you want to access some of your money it is very difficult to sell part of the property, like just the bathroom, or a window – you sell all or nothing. The costs of both buying and selling with legal fees, stamp duty, real estate agent fees, etc. go into the thousands. When Claudia and I moved in 2011, the total costs for selling the townhouse and buying our house were in excess of $42,000. And that was before we discovered our new house had active termites.

For Sale – One bathroom window with fly screen and lock. Beautiful views. Ideal for first home buyer.

It is very easy to be ripped off by a real estate agent when buying or selling property, most people don’t even realise when they have been. I refer anyone who is considering buying or selling real estate to The Jenman Group. If you are about to sell property, don’t do so without first obtaining a copy of the Homesellers’ Protection Guarantee. This is a document that is added to and becomes part of your real estate agent’s agreement, also known as a sale contract. Its sole purpose is to protect sellers from the tricks and traps that many agents use on them. The guy who wrote the Homesellers’ Protection Guarantee, Neil Jenman, is a former real estate agent who now speaks out against those in the industry who rip unsuspecting people off. He is despised by many real estate agents and admired by others. An ad for his website says: “Crooks hate him, consumers love him, find out why.”

Jenman started his own system of selling real estate which has at its core the highest standards of ethics in dealing with consumers, called The Jenman System. The only real estate agents who are accredited with this system are Jenman Approved agents and they are located in all Australian states and territories. The Homesellers’ Protection Guarantee is free and you do not have to go through a Jenman approved agent to use it.

If you are in the market to sell a home and you are considering selling at auction you need to know what you are getting yourself in to. Before you make a decision read this Jenman article titled 9 Reasons Auctions Get Lower Prices. That’s the abridged version. The book below is unlike any other you are likely to come across. It’s not designed to be read cover to cover, rather Jenman has written it in numbered reasons so that you just read enough until you are convinced that selling your home at auction is a very bad idea.

FURTHER READING: Neil Jenman is also the author of the books 88 Reasons: essential reading for those considering selling at auction; and Don’t Sign Anything: a frightening account of real estate in Australia.

FURTHER READING: Neil Jenman is also the author of the books 88 Reasons: essential reading for those considering selling at auction; and Don’t Sign Anything: a frightening account of real estate in Australia.You have heard all the negatives but decide to go ahead and invest in property. There are a couple of ways of doing so. The most common is direct ownership of residential housing bought and sold through a real estate agent. You can also own commercial premises directly, though you would expect the purchase price to be higher than that of residential property. Or you can invest in property through a syndicate, trust or managed fund. These vary greatly but all work on the premise of a number of people pooling their money to each purchase a portion in the properties owned by the trust. Minimum investment amounts in these will vary but can be from as little as $1,000 and there may be restrictions on how and when you can access your money, but they’re a good way to diversify a property portfolio.

Some investors buy residential property with another party, I don’t mean a partner or spouse, I’m talking about a family member or close friend. This is not a good way to invest money because it can complicate matters, especially when one person needs to sell the property and the other person is not in a position to be able to. If you are a couple you are hopefully working together towards a common goal so owning a property together should work ok.

If direct ownership of property is the way you decide you want to go, beware of guaranteed rental returns. This will be advertised as a guarantee to pay rent for the first 1-3 years on newly built projects to try and entice buyers by making them believe the rental market is so strong that tenants are already lining up to live in the new units. In reality though, the purchase price has been increased by the developer to include the first year, two or even three years’ rent (which the developer pays you from the money you have already given them). Guaranteed rental returns are nothing more than a way of selling real estate at inflated prices and they are a massive rip off.

Shares

This asset class includes pretty much everything that can be bought or sold on the sharemarket (which is also known as the stockmarket or equity market). Most commonly, shares refers to ordinary shares in a company – they’re the ones you see in the finance report on the news. People who hold these shares own a small part of the company concerned and are entitled to receive a cut of that company’s profits as a dividend payment. Other items traded on the stockmarket include preference shares, warrants, options and futures. The only thing I have to say about these, especially futures, is that they can be more risky than ordinary shares and should only be traded by people who know exactly what they are doing. With ordinary shares you could expect returns of roughly 9-14% per annum over the long term. Shares are a long term investment and should be held for 7-10 years or longer.

Trading in futures is so hit and miss that even the professional futures traders get something like 70% of their trades wrong (meaning the traded commodity heads in the opposite direction to what they thought it would). If the experts get it wrong most of the time, do you reckon an amateur can be on the money?

Contracts For Difference (or CFDs as they are marketed) are in the same category as futures. Just because they have schmick marketing with graphs going upwards and people smiling, doesn’t mean they are not incredibly risky. Before you look into CFDs, remember the wisdom of those knights from Monty Python and the Holy Grail – “Run away, run away!”

The advantages of shares are: They have the highest returns of the three asset classes over the long term. Returns vary depending on many factors, including the sharemarket, business cycle and broader economy. You can sell them and have the money in your bank account very quickly (in three days for most companies). Many shares have tax advantages – the Australian shares with the taxation advantage are the ones with what’s known as franked dividends. Shares have both income (in the form of dividends) and capital gains as the share price increases, therefore they’re a good hedge against inflation. You may use the income from dividends to purchase more shares in the same company, which is known as dividend reinvestment. There’s a lot of information available about a company’s shares, and it is possible to sell a few of your shares to access some money while you hold on to the rest of them.

The disadvantages are: They are the highest risk and have the highest level of volatility of the three asset classes. The returns are not guaranteed and some companies may not pay a dividend if business is not going well. Some overseas companies never pay dividends so you have to rely entirely on the increase in their price to see any return. You must buy through a share broker whether in person, over the phone or on the internet and you really should get a broker’s expert advice before you buy. You need their advice because all the information out there on individual companies makes it very confusing for the non-professional to work out what is a good purchase. The fees for no-advice brokerage are generally fairly low. And lastly, because of their large risk, a bad experience with shares can turn off an inexperienced investor very quickly. I know of many cases where people have bought shares in some no-name, dodgy company on the advice of their hairdresser or mechanic, only to see them lose their money and be scared off from ever investing in the sharemarket again. I don’t cut people’s hair, I don’t fix cars, and I don’t tell people which company’s shares to buy. There’s a bloody good reason for that – I’m not an expert in these areas.

It is easy to be swayed to purchase an investment, any investment, by someone who has been successful in investing in that particular asset class. Unless you are the same age, same marital status, have the same number of children, the same income and an ability to take the same level of risk as the successful person, DON’T think that because it worked for them then it will automatically be the same for you.

There are a few different ways to invest in the sharemarket. You can purchase shares through a full service stock broker, who will be fairly expensive but they will advise you which companies they believe are best for you. Or you can do your own research on various companies then buy those shares through a discount broker who will be much cheaper but won’t give you any advice. Online brokers these days can be very cheap, charging prices that start at $0 per trade (yes, there are asterisks attached to those ones). You may be fortunate enough to receive shares in a company float, for example, many people received shares in AMP, the NRMA and NIB back when they were first listed on the stock exchange. And you can invest in shares indirectly by having money in a managed fund.

To learn more about shares, the Australian Stock Exchange has a bunch of online courses they offer for free. And for more on everything investment, including shares, property, cash and fixed interest the non-profit Australian Shareholders’ Association is a great resource.

Now I have a quick video to show you which attempts to explain a little better the concept of risk.

That short haircut was a risk. It, ah, didn’t pay off. When I first shaved my head everyone said “You’ve got a good shaped head” so I kept my head shaved for months. Then when I grew it back all I heard was “You look so much better with hair!” So I gathered from that experience that nobody will be honest with me when I have to do the inevitable head shave as my hair thins even more in the coming years.

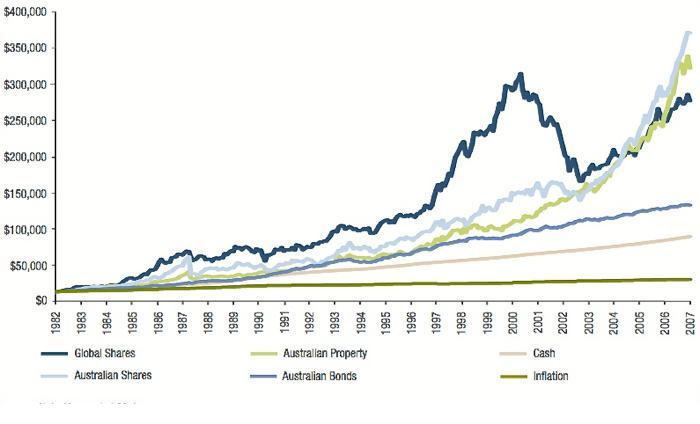

Debt Smart strategies for debt management 2007/2008 brochure, MLC.

The graph above shows the comparison of the compounding effect of $10,000 invested in the different asset classes of international shares, Australian shares, Australian property, bonds and cash. The bottom line is inflation. The bonds and cash lines could be averaged out to give one line – being cash and fixed interest, which would be the lowest return but a very smooth and predictable line. As you can see, over the long term, the highest returns have gone to the growth assets of shares and property. If you had the foresight (and money) to invest $10,000 in growth assets back in 1982 they would have had a very bumpy ride over the 25 years to 2007 as they are high risk. But they would have grown to be worth between $270,000 and $370,000. This graph assumes that all income from investments has been re-invested and is a snapshot taken just before the global financial crisis. Since 2007 there have been massive movements in both international and Australian sharemarkets, first down, then back up again and a fair bit of sideways movement too. For a more recent graph covering the years from 1993 to 2023, look at Vanguard Investment’s website.

Managed Funds

Managed funds are not a separate asset class, they are an instrument through which to invest. I have included pros and cons for them because they tend to be misunderstood.

Managed funds are investments where money from a number of investors is pooled together to buy many assets and handed over to the fund manager who deals with the investments on their behalf. When you invest money in a managed fund, you purchase units in the fund and it is the unit price you want to see going up. The vast majority of superannuation money in Australia, and probably all the super held by you if you don’t have a Self Managed Super Fund (more on that in the Superannuation topic), is invested in managed funds. Most managed funds have holdings in more than one asset class, e.g. a growth fund might have money diversified across shares as well as property, while a balanced fund will have money spread across shares, property and cash. The returns, risk levels and taxation of individual funds will be reflected by the asset classes the funds are invested in. So you can expect an Australian share fund to have a similar return as well as a similar risk level to the Australian sharemarket as a whole.

The advantages for managed funds include: Easy access to markets which many investors would not have the money to invest directly in. You can start with as little as $1,000 in most funds, $100 in some. This compares to $15,000 – $20,000 for a decent starting amount for a personal share portfolio, or around $500,000 – $600,000 for an investment property. It should take only about a week for you to get the money from a managed fund into your bank account when you want to sell your units. The funds are managed by professionals who (should) know what they are doing – the only investment decision you have to make is which managed fund to put your money in. The fund manager makes all the decisions in regards to buying shares of companies they reckon will go up in value, and selling those they reckon are about to drop. You achieve a very good diversification, or spread of your money, with managed funds as it is put in so many different investments.

Another great advantage of managed funds is that most allow investors to set up a regular savings plan. This works where you elect to invest a set dollar amount into the fund, for example $100 per month.

Dollar Cost Averaging

| Month | Unit price | Units bought |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | $1.00 | 100.00 |

| 2 | $0.75 | 133.33 |

| 3 | $1.25 | 80.00 |

| 4 | $0.80 | 125.00 |

| 5 | $1.20 | 83.33 |

| 6 | $1.00 | 100.00 |

| $1.00 | 621.66 |

The table above shows a six month period where the unit price in a managed fund is going up and down from one month to the next. Because it’s going up and down so much we can assume it’s a growth fund invested in mainly shares and property. Investing this way is called dollar cost averaging and it effectively means you buy more units when the price is low and less when it is high. As you can see from this example, the average unit price over the 6 months is $1. It is also the price in months 1 and 6. If you had bought $600 worth of units in either of these months you would only have 600 units, but spreading the purchase over the 6 months sees you with 621 units. This is only an example and in reality it may not work out exactly like this. But, dollar cost averaging can work very well as part of an overall savings and investment plan, particularly when you combine it with reinvesting any income the fund makes.

You have the choice of taking any income the fund earns as a deposit into your bank account, or a cheque, or you can purchase additional units in the fund. To get the real benefit of compounded growth (explained in detail at the end of this topic) you need to invest regularly. The simplest way is to have a regular savings plan with the income reinvested in a managed fund. Superannuation funds know this, which is why your super is invested in exactly this way. So if you think you’ll never have money compounding with dollar cost averaging, well, you probably already do.

Please don’t underestimate the power of compounding, especially when combined with regular saving. This strategy has helped to pay off many mortgages (including my first mortgage) and means thousands of self-funded retirees are living a comfortable life. It’s the strategy that’ll be looking after the vast majority of Aussies when we hit the age where we take an active interest in lawn bowls and Bridge. Especially Bridge! I’m so excited – I can’t wait!

The disadvantages of managed funds are: Many funds hit you with fees when you put your money in, some hit you when you take your money out, and all of them charge an ongoing fee for looking after your money. Just because they charge a fee is no guarantee that they will perform any better than what the market is returning. In fact many funds do worse than the very markets their expert managers are paid to beat, and you still have to pay the ongoing fee. You have no say as to which assets are bought and sold and when.

How do you go about investing in managed funds? If you know the fund you want to be in, you can contact the fund manager directly and have a prospectus sent to you. You will probably pay the full amount of any entry fees if you do this. If you are not sure which fund you want, you can buy through a managed fund broker.

There are lots of managed funds around.

This is probably a good option as there are around 3,500 managed funds to choose from in Australia. The entry fees may be reduced, depending on how much work the broker does to find a fund that you will invest in. Some managed fund brokers may allow you to search their database to shortlist potential funds. A very cheap online managed fund broker can be found at InvestSMART.

Or you may invest in a managed fund via a financial planner. The financial planner who charges a set fee for their service will likely rebate to you any entry fee to the managed fund you would pay.

Vanguard Investments is an index fund manager. Investing with them can mean investing across the 200 companies that make up the ASX 200 index, for example, with your money being spread in the proportion in which they make up that index. WTF? If BHP makes up 6% of the ASX 200 (it’s a massive company) then 6% of your money is invested in BHP. Most companies in the top 200 make up only tiny percentages of it – only around 20 have a capitalisation of more than 1%. An index fund will never out-perform the market, it will only ever have returns in line with the market, minus a small amount for fees. In contrast, active (ordinary) managed funds will always try to achieve higher returns than their competitors, and this usually means trying to out-perform the market. The harder they try, the higher their fee. The higher the fee, the less likely they are to outperform the index, net of fees.

Vanguard also offers a free weekly email newsletter called Smart Investing which contains some good info. Vanguard says that average index funds consistently outperform their non-index brothers, while having lower fees. From what I have seen, year after year, this is accurate. You just need to know that Vanguard is biased towards index funds as it’s their bread and butter. I’m not saying you should or should not invest with Vanguard, but you can certainly draw on their resources for learning.

Growing in popularity, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are very similar to index funds, the biggest difference is that the ETF is itself listed on the sharemarket. They must be bought and sold through a broker, and they have lower fees than even index funds – around 0.5% management fee for an ETF, around 1% for an index fund (this compares well with the average fee for an active managed fund of around 4%.) The advantage of an index fund over an ETF is that you can automatically reinvest index fund distributions and they are great for dollar cost averaging, but you can’t set up the same automatic reinvestment with ETFs. You can choose to invest on a regular basis with an ETF but you’ll be hit with brokerage every time.

Return needed for an investment to outgrow the interest on a non-tax deductible loan.

If you have a non-tax deductible loan such as a mortgage or car loan, as well as an investment (or you are considering an investment) you must decide whether you would be better paying more off the loan, or investing. To do this you need to take into account the effect of tax on your investment by using this formula:

ATR = (1-T) x R

Where ATR is the After Tax Return, R is the gross return and T is the marginal tax rate (expressed as a decimal).

E.g. You have a loan at 7.5% p.a. and an investment currently returning 9% p.a.. Your marginal tax rate is 34.5% (including Medicare levy of 2%).

ATR = (1- 0.345) x 9 Remembering the basics of high school maths, work out the figure in brackets first.

ATR = 0.655 x 9

ATR = 5.895

So the after tax return of your investment is 5.895% which is 1.605% lower than the interest you are paying on the loan. In other words, your loan is costing you more than your investment is earning for you. Your investment return would have to offer a guaranteed after tax return of more than 7.5% before you could say it would be better to invest than pay off the loan with the money. Investments like this are risky and hard to find. The following table is a quick reference guide to the after tax returns, for all marginal rates, for investments returning between 3% and 9% p.a.

After Tax Returns on Investment

Marginal tax rate (includes Medicare Levy of 2%) 3% return 4% return 5% return 6% return 7% return 8% return 9% return 0% 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 21% 2.4 3.2 4 4.8 5.6 6.4 7.2 34.5% 1.965 2.62 3.275 3.93 4.585 5.24 5.895 39% 1.83 2.44 3.05 3.66 4.27 4.88 5.49 47% 1.59 2.12 2.65 3.18 3.71 4.24 4.77 Please note: 1) The table is relevant for loans that are being paid with after tax money. E.g. money that would come from your bank account after you have already paid tax on it, NOT loans that are being paid off as part of a salary packaging arrangement with your employer – more on that in the Taxation topic; and

2) This table is relevant for cash and fixed interest investments only, as 100% of the returns in this asset class are taxed at marginal rates. For property and shares the return is a combination of income and capital gains, which is treated differently for taxation purposes. However, as the returns are best guaranteed for people wanting to compare an investment to a non-tax deductible loan, I have assumed an investment in the only asset class with guaranteed returns – cash and fixed interest. Does this mean that if you have a mortgage then you shouldn’t invest in growth assets? No. But remember that growth assets go down as well as up, so if you have money in a share portfolio that is losing value as your mortgage interest rate is going up and costing you more, it takes balls of steel* to keep your head and hold onto the shares long enough for the good years to make this strategy work. In terms of ability to handle risk like this, the vast majority of people can’t handle it. *Women can have balls of steel.

Next Sub-topic: Investment 3 >>

Investment 2 Resources

- Government guarantee for deposits

- Australian government bonds

- The Jenman Group

- Jenman’s Real Estate Homeseller’s Protection Guarantee

- 9 Reason Auctions Get Lower Prices

- Australian Stock Exchange online courses

- Australian Shareholders’ Association

- Vanguard’s Index Chart

- InvestSMART

- Vanguard’s newsletter

- 88 Reasons and Don’t Sign Anything by Neil Jenman