Budgeting

Time for a dirty word – Budget – Anita Bell, Your Mortgage and How to save $50,000 to $250,000

A budget is a plan of income and expenditure – it’s about knowing where your money is coming from and going to, with you being in control of your finances rather than having your money controlling you. We look at income first.

Income

It’s probably fair to say that nearly all of us think our current income is not enough. For people relying on a government pension that is probably a true statement, but for those in full time paid employment here is a strange fact. Many people, no matter what they are paid, believe they would be financially comfortable if they were earning about 10% more than they currently are. It doesn’t make sense that someone earning $50,000 is seeking the same 10% pay rise as someone earning $500,000. It only starts to make sense when you see what they do with their money.

A survey conducted by Sunsuper around Australia found that of those who were dissatisfied with their finances, 51% said it was due to ‘Not earning enough money’. ‘Bad luck’ polled 24%, while just 2% said ‘Having too much debt’. Source: ‘Lady Luck to Blame for Financial Woes?’ On The Spot magazine, Issue 13.

I am not going to put an emphasis on increasing your income because quite often our income is dictated by our age, experience, qualifications and the type of work we do. None of these are easy to change and contrary to what many people believe, there is no reliable way to get rich quick.

I am also not about to suggest that you should attempt to increase your income by getting a second job. You may be thinking “That’s easy for you to say Nick, this course is your second job.” Um, yeah fair point. But believe it or not, when I wrote Financial Freedom I didn’t do it as a way to increase my income, it began as a hobby (how big a nerd am I?). Upon my insistence, CIT Solutions, the company I was employed by to present the course face to face, paid me $20/hour. Over a six hour period of teaching I’d end up with $120 per course, regardless of the number of participants. I charged CIT Solutions much less than they wanted me to take because I needed to keep the cost of the course down as low as possible to make it affordable for those who most needed the information. I could hardly sit there in front of a bunch of people and tell them that they should save their money if it cost them a mint to hear me say it.

These days, with this website, I only receive an amount from people who choose to donate, which means I am under a financial incentive to have as many people visit the site as possible. To get visitors I rely heavily on recommendations and referrals from people like yourself. If I am relying on you, I need to be able to make you want to send a link for this website to people you know by making this course relevant, interesting and worthwhile. You be the judge. (If you’re thinking I make a motser from donations let me put it to you this way – if I were to retire today and live off the earnings from this site, I’d want to die tomorrow. Before breakfast.)

Increasing your income is nowhere near as easy a thing to do as decreasing your spending and saving the leftover. Many people spend years trying to get a pay rise when they could end up with more money in their pocket by changing the way they shop.

A dollar saved is worth more than a dollar earned. If you save $100 it is worth more to you than doing $100 worth of work, simply because your work will be taxed.

A budget can be for any time period with the most effective budgets being over a pay period (weekly, fortnightly or monthly) or over a year. We’ll look at a budget that includes everything earned and spent in a year, divided into fortnightly portions.

The reason we look at fortnightly budgeting is because government payments are made fortnightly. It’s just an example, do what works best for you. If you are self-employed you may need to have a budget over a quarterly or annual period. If you already have a budget and it is broken down into weekly, fortnightly or monthly parts, include an annual column as well, because looking at expenditure over a year can be more of an eye opener for where you may be spending too much.

I am making an assumption here that everyone has some form of income.

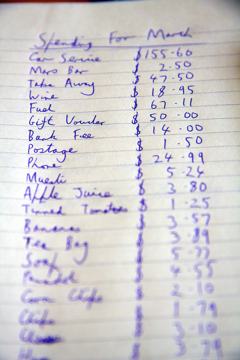

It is very important when budgeting to use accurate figures wherever possible, not what you think you earn and spend.

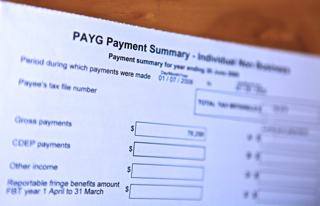

First thing to look at in your budget is your gross income. This is your income before tax is taken out and includes salary or wages, government payments, interest and investment income. If your situation hasn’t changed much in the last 12 months or so you should be able to find these figures in last year’s tax return (assuming you did your tax last year).

Ever looked at your Payment Summary (it used to be called a group certificate) at the end of the financial year and asked yourself where all your money went? If you answered yes, you need a budget.

Some budgets work with net or after tax income, but I like to include tax so that you are more aware of it and can give more thought towards reducing it. You need to have tables for income, savings, essential expenditure, desirable expenditure and totals for all of these. They should look something like the following (feel free to add or subtract items from essential and desirable expenditure to suit your situation):

Budget Template – Income

| Income | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Wage/salary | $ | $ |

| Interest | $ | $ |

| Govt payments | $ | $ |

| Investment income | $ | $ |

| TOTAL INCOME | $ | $ |

If you don’t like my dodgy budget templates then use this one. You can save and fine tune your budget with this spreadsheet as much as you like and it includes a version to allow access across multiple devices.

On the point of government payments, if you think you may be entitled to one, then apply for it. Some people feel too proud to accept money from the government, but I reckon you should look at it like this: when it comes to paying tax, the government takes from you what they’re entitled to. Therefore, for government payments it is only fair that they pay you what you are entitled to receive.

If you have a family, check out the family pages of the Services Australia site. They have info on things like the Paid Parental Leave scheme, Child Care Subsidy and Family Tax Benefits Part A and B. Visiting this site can mean money in your pocket. There’s plenty more detail on these family payments in the Kids And Money topic.

Expenditure

The expenditure side of the budget is much more detailed than the income. For your budget to work it must contain: savings, essentials (or needs), desirables (or wants), and emergencies. It has to contain these and it must be flexible and/or realistic, especially when you are getting used to a big change in the way you are looking at your budget or if you have never really budgeted before. If it’s not realistic, it’s not going to work.

Savings

Savings are the most important part of your budget. They are not essential to live, but they are essential for you to achieve your financial goals. Savings are concerned mostly about the spending side of the budget. In particular it is about not spending so much that you have nothing left, no matter how much money you had to start with.

Budget Template – Savings

| Savings | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| TOTAL SAVINGS | $ | $ |

The term ‘saving money’ can be interpreted two ways. You can save money at a sale where you spend less than the previously marked price. This is the type of saving that the marketing industry wants you to do. Or you can save money by setting aside a proportion of your income for the future. This is the type of saving you need to do.

The experts say you should save 10% of your income. I don’t quite agree with this. I think you should try to save at least 10% of what you earn, more if you can afford it. This does not mean that you should save 10% of your income if you are on track to pay off your entire mortgage in 5-6 years, or rid yourself of your car loan and credit card debt within 18 months, because by paying off your debt so quickly you are in effect saving more than this 10% amount anyway. If saving more than 10% sounds like an impossible dream, you need to pay special attention to the Savings topic.

Australians used to be good savers. Back in the 1970’s the average savings rate was 12.5%. This dropped to an average of 10.4% in the 80s, then to 4.9% in the 90s. Throughout the noughties, the savings rate was an average of 0%. The shocking thing is that these figures include the savings from compulsory superannuation contributions made by employers. During the years of the Global Financial Crisis, the rate of household savings shot back up to peak at around 13.5% before dropping to single figures again. Then when the economy went sour as COVID first hit, the savings rate briefly skyrocketed. Unfortunately it appears the savings over the GFC and COVID were just brief spikes in an otherwise long-term falling trend.

When’s pay day?

If the amount that you are currently saving equals what is left in your bank account or wallet after you have done all your spending, chances are this amount is zero dollars. If this is the case you must start to look at your money in these terms: income minus savings equals the amount you have left for spending. And for those of you who want to cheat, the 10% you need to be putting aside for savings are completely separate from the contributions your employer makes to your superannuation. As you will see in the Superannuation topic, you can’t access super benefits until you reach age 60.

This next table shows the effect of saving 10% of your earnings, with compounded returns at a rate of 7%. Savings have been made fortnightly and interest has been paid quarterly. There has been an assumption of $0 savings at the start of the time period.

| Annual Income | $ Per Fortnight | After 5 Years | After 10 Years | After 20 Years | After 30 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30,000 | 115 | 17,195 | 41,311 | 122,577 | 282,438 |

| 40,000 | 154 | 23,026 | 55,321 | 164,146 | 378,221 |

| 50,000 | 192 | 28,708 | 68,972 | 204,649 | 471,548 |

| 60,000 | 231 | 34,539 | 82,982 | 246,219 | 567,331 |

| 70,000 | 269 | 40,221 | 96,632 | 286,722 | 660,659 |

| 80,000 | 307 | 45,902 | 110,283 | 327,226 | 753,986 |

| 90,000 | 346 | 51,734 | 124,293 | 368,795 | 849,769 |

No taxes have been taken into account, but you can see that for a relatively small fortnightly saving, it really can add up to become a large amount over time. Where can you earn a return of 7% on your savings? We look at that in the Investment topic.

If you live in an area that has decently fast internet access, consider going VOIP for your home phone. It can mean free local and national calls, as well as free Skype calls to anywhere in the world.

Needs

Essentials, or needs, are the things we can’t do without. This includes rent, board or mortgage payments, rates, repairs, food, clothing, transport (including rego, vehicle repayments, petrol and parking, or public transport and taxi fares, etc.), insurance, phone, gas, electricity, water, health (including doctor, dentist and chemist) and tax. If you forget to include tax, there will be a big hole in your budget. All of these are things you need to live in today’s society.

Insurance being classified as an essential may come as a surprise to you. Not all insurances are essential as you’ll see in more detail in the Insurance topic.

Budget Template – Essentials

| Essentials | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Rent/mortgage | $ | $ |

| Rates | $ | $ |

| Food | $ | $ |

| Clothing | $ | $ |

| Transport | $ | $ |

| Insurance | $ | $ |

| Phone | $ | $ |

| Gas | $ | $ |

| Electricity | $ | $ |

| Water | $ | $ |

| Health | $ | $ |

| Tax | $ | $ |

| TOTAL ESSENTIALS | $ | $ |

If you find all your expensive annual bills hit you at once, you may be able to spread out some bills over the year.

Wants

Desirables, or wants, are things we can live without but would prefer not to. Yes, this list might seem harsh, but it includes extravagant Christmas and birthday presents, cigarettes, alcohol, holidays, sports, entertainment (including things like gaming consoles, tablets, and subscription TV), hobbies, pets and my personal vice in its own category – chocolate. Having a budget work better for you means finding a balance between your needs and your wants and spending less on these non-essentials.

Budget Template – Desirables

| Desirables | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Christmas/birthday presents | $ | $ |

| Cigarettes | $ | $ |

| Alcohol | $ | $ |

| Holidays | $ | $ |

| Sports | $ | $ |

| Entertainment | $ | $ |

| Hobbies | $ | $ |

| Pets | $ | $ |

| TOTAL DESIRABLES | $ | $ |

It is very important when saving money to be able to distinguish between the things we need and the things we want. Technically there are only five things we need to live: oxygen, food, water, shelter and access to medicine. But there is so much affluence in Australian society that we are led to believe we need much more. Thank you Mr advertising industry.

Source: Affluenza: When Too Much is Never Enough by Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss (Allen & Unwin, 2005)

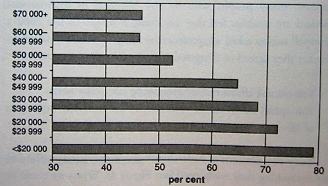

This table shows the proportion of Australians who agree that they cannot afford to buy everything they need, split into income groups. Overall, 62% of Australians said they can’t afford everything they need. It’s amazing that this includes nearly half of the richest 20% of households in Australia: the richest people, living in one of the world’s richest countries, said they can’t afford everything they need.

Everybody has pretty much the same needs. They don’t change much from person to person and shouldn’t change as your income increases. But your wants can get out of hand, particularly when you see people with a higher standard of living than yourself and you aspire to that higher level. It’s ok to want these things and it may be ok to have them. Just keep in mind that getting all the things you want probably won’t make you happier, especially if you are going into debt to buy them. In fact it is our lack of ability to distinguish between what we really need, and whether we can afford to buy what we want, that lies at the heart of the debt problems we looked at in Debt Elimination.

FURTHER READING: Affluenza: When Too Much is Never Enough by Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss (Allen and Unwin, 2005): A fascinating insight looking at why, given Australia’s economy has been going so well, Australians are not becoming happier.

FURTHER READING: Affluenza: When Too Much is Never Enough by Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss (Allen and Unwin, 2005): A fascinating insight looking at why, given Australia’s economy has been going so well, Australians are not becoming happier.Emergencies happen when we don’t want them to and are made worse when we cannot afford to pay for them. How much you should have set aside varies greatly depending on your situation, but a very rough guide is to have at least $3,000 per person. In other words, at least $6,000 for a couple, $9,000 for a family of 3. This will not cover every emergency but it should at least prevent you from having to borrow to get yourself out of strife, or stop you from having to eat two minute noodles for dinner for a couple of months. Some pundits say you should have as much as six months income set aside for emergencies. I reckon this amount is probably ideal, but it’s bloody unrealistic for the vast majority of Aussies.

I did mention in Debt Elimination, under Pawnbroker and Payday Loans, that in an emergency you can go into debt using a credit card. However, this should only be done in the interim period when you don’t have enough emergency money saved and set aside.

Budget Template – Totals

| Income/Expenditure | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Total income | $ | $ |

| Total essentials | $ | $ |

| Total desirables | $ | $ |

| Total savings | $ | $ |

| SURPLUS | $ | $ |

The following is an example of a budget for a person earning a salary of $58,000 a year.

Example Budget – Income

| Income | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Wage/salary | $58,000 | $2,231 |

| Interest | $104 | $4 |

| Govt payments | $0 | $0 |

| Investment income | $0 | $0 |

| TOTAL INCOME | $58,104 | $2,235 |

They have $8,000 in an online savings account which earns them $104 per annum interest. I must emphasise that some of the figures in this budget may seem to you to be about right, too high or too low. It doesn’t really matter if this differs a lot from your income and expenditure because everyone’s budget is different, but I have tried to make this budget as realistic as possible. It’ll also differ a bit depending on where you live – residents of Launceston would spend more on gas for heating than those of you in Cairns.

Example Budget – Savings

| Savings | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| TOTAL SAVINGS | $ 5,800 | $ 223 |

The first thing that comes out of their budget is their savings. At $5,800 they are achieving 10% per annum, which they budget as $223 per fortnight. The key part of their budget is now done. Simple hey?

Example Budget – Essentials

| Essentials | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Rent/mortgage | $ 13,800 | $ 530 |

| Rates | $ 0 | $ 0 |

| Food | $ 5,440 | $ 209 |

| Clothing | $ 1,603 | $ 62 |

| Transport | $ 3,250 | $ 125 |

| Insurance | $ 1,686 | $ 65 |

| Phone/Internet | $ 1,643 | $ 63 |

| Gas | $ 526 | $ 20 |

| Electricity | $ 2583 | $ 99 |

| Water | $ 0 | $ 0 |

| Health | $ 832 | $ 32 |

| Tax | $ 9,350 | $ 359 |

| TOTAL ESSENTIALS | $40,713 | $1,565 |

They spend nothing on rates and water so it means they are renting. At $265 a week rent they are living in a share house. They drive a car and pay a few thousand in income tax. You may find it easier to have two money columns being annual and per pay period, dividing the annual bills by the number of times you are paid to get the amount you should be budgeting for, but not actually spending, each pay period.

If you live in a share house where you need to be splitting bills and find it hard to keep track of who owes who what, Settle Up can help you out.

Example Budget – Desirables

| Desirables | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Christmas/birthday presents | $ 875 | $ 34 |

| Cigarettes | $ 0 | $ 0 |

| Alcohol | $ 1,305 | $ 50 |

| Holidays | $ 1,500 | $ 58 |

| Sports | $ 0 | $ 0 |

| Entertainment | $ 6,200 | $ 238 |

| Hobbies | $ 1,690 | $ 65 |

| Pets | $ 0 | $ 0 |

| TOTAL DESIRABLES | $ 11,570 | $ 445 |

As you can see from their desirable expenditure, they do not smoke (which is good for their health), don’t play any sport (which is bad for their health) and the landlord doesn’t allow any pets. Some expenses can go in more than one column, e.g. your hobbies, alcohol consumption and entertainment may all be the same thing.

*Note* A couple of weeks after recording this video, cigarette prices went up and they have continued to rise significantly since. The updated final figure would now be around $51,000. If you’re a non smoker, punch in the figures from your chocolate/retail therapy/alcohol/porn vice.

Example Budget – Totals

| Income/Expenditure | $ Annual | $ Fortnight |

|---|---|---|

| Total income | $ 58,104 | $ 2,235 |

| Total savings | $ 5,800 | $ 223 |

| Total essentials | $ 40,713 | $ 1,566 |

| Total desirables | $ 11,570 | $ 445 |

| SURPLUS | $ 21 | $ 1 |

The last thing to do with your budget is subtract your savings and expenses from your income which will hopefully leave you with a small surplus (or your budget could balance, but hopefully it’s not in deficit). So, this is an example of near perfect budgeting but it’s not written in concrete and will change as your financial circumstances change.

This is all done in the ideal world, where you write down everything you earn and everything you spend over a 12 month period. You ensure that you’re not putting too much into any one area whilst remembering to save 10% (which of course doesn’t include emergencies). You must then ensure you stick to it, otherwise it’s just a bunch of numbers written on a few pieces of paper.

Alternative budgeting

You may choose to have savings deducted automatically from your pay to an account that does not have easy access (so you are not tempted to withdraw the money as cash from an ATM or transferred over the internet. Yes, I’m talking about the old fashioned way of having to withdraw the money – in the branch, over the counter). You will still need to keep track of those more expensive annual bills I spoke about in the earlier video above with this method, and one way to help with this is to have a second amount deducted and placed into another account to be used for large bills only. You can then go and spend the rest of your income on whatever you like.

It’s a great idea to open a bank account that has at least 10% of your pay go into it automatically for savings on pay day. Use these savings for the things written on your list of goals.

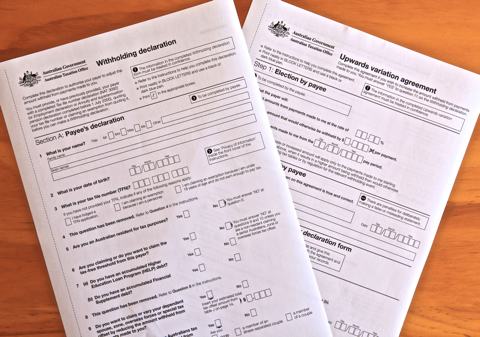

Another way of forced savings is to not claim the tax-free threshold or to elect to have a stated greater amount of tax taken from your pay. This involves filling out one of these withholding declaration forms you can see on the right, and crossing the box stating that you do not wish to claim the tax-free threshold. This will effectively mean that you are temporarily taxed more each pay period and it’s not appropriate for people wishing to claim certain other entitlements with their tax – make sure you read the form thoroughly and understand it before you decide on this path.

The disadvantage in doing this is that you don’t get access to this extra taxed money until the end of the financial year, after you have submitted your tax return, and the tax office won’t pay you interest on the money like a bank account would. The advantage is that it’s a form of forced savings from which you should get a decent sum back from the taxman sometime around July. But you do have to do your tax to get this money, if you don’t, the tax office will hold onto it until you submit your return.

If you’re one of those people who is worried about writing a budget because you don’t know where your money goes, a great way to see where it has gone is to write down everything you spend in a month. Then look back on this list and separate wants from needs and see where you could achieve some savings. This is basically doing a budget after the fact rather than before it, but do whatever works for you.

As I said earlier, in the ideal world, you know everything you are earning and spending, with a written budget, balancing needs and wants, with savings accumulating regularly, that you stick to and is never blown. If you can do it this way, great. But it’s not how Claudia and I budget. I’m far too lazy for that.

We simply ensure that we spend less than we earn and save the amount leftover (yep, at least 10%). As long as you follow that simple rule, perfect budgeting where every cent is tracked in a spreadsheet is not necessary at all.

And when it comes to saving money by spending less, I’ve got a few tips in the Saving topic….

Budgeting Questions

To budget effectively, the most important part of the budget is:

- Savings

- Essential expenses

- Desirable expenses

- Emergencies

- Income

The amount you should save is:

- 9.5% super of gross income

- 10% of net income, including super

- at least 10% of net income, not including super

- at least 10% of gross income, not including super

The easiest way to remember the difference between gross and net income is to imagine your entire income (gross) made up of notes and coins, being put into a net. The stuff that falls through the gaps is tax, the amount you have left is the net income.

Your budget should be broken into which time period?

- weekly

- fortnightly

- monthly

- per pay period

- annual

Budgeting Resources

- MoneySmart’s budget template

- Services Australia

- Settle Up

- Withholding Declaration Form

- Affluenza by Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss